I've been thinking quite a bit about estimations and our general obsession with getting them "right". After all, we need to know when the project will be done. And we need accuracy. Knowing the entire project will be done before the end of the third quarter isn't good enough. We need to know that the project will be done this month or this week or perhaps even on this specific day.

Through consistency, we attempt to achieve predictability.

I've watched teams put a great deal of effort into improving their estimates. I've seen teams compare stories from this sprint to stories from prior sprints to try to maintain consistency. I've seen teams use a reference story for a single point. When estimating, they look at the reference story and then estimate all others compared to it. These seem like decent practices. The goal of these practices is consistency. Through consistency, we attempt to achieve predictability.

But one thing I've never understood is the notion of estimates versus actuals. Here we look at the original estimate for a story and we then estimate again once the story is complete. The idea here is that the estimate upon completion is an actual. This provides us a learning opportunity whereby we can improve our estimates going forward. This, to me, is a flawed approach. To illustrate my point, let's look at estimations from a slightly different angle.

Estimating Sudoku

Indulge me for a bit here. Writing code is really problem solving. Sudoku is (clearly) problem solving. Admittedly, sudoku is far more simple than writing code. Simple in terms of strictly constrained and with very few possible solutions (often one solution). If we can agree that sudoku can serve as a simple model for writing code, then please do read on.

I have a sudoku game on my phone. It breaks the games down into four categories; easy, medium, hard, and expert. Clearly, the games are all on the same size grid with the exact same rules. The difference between these games is merely the number of seeded answers and their locations on the board. These two factors make a game more or less difficult to solve. I don't know that a medium is twice as difficult as an easy, but I am certain that a medium is more difficult than an easy.

Actuals

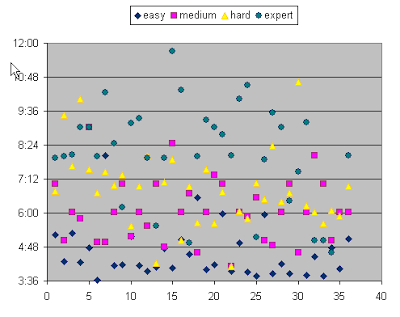

I've played hundreds of sudoku games on my phone. I've played each level of difficulty at least 50 times. And the game has tracked my actual time to complete for every play. The following graph shows the time to complete for 40 games at each skill level. The y-axis is the time to complete. The x-axis is the number of games.

At point 6 on the x axis, the easy story takes nearly 8 minutes to complete. This is well outside the normal effort for an easy. In fact, it exceeds the average for a medium. After completion of this puzzle, were you to have asked me, I might have concluded that it was actually a medium or even a hard. But the truth is, it was an easy. For some reason, I struggled to solve it. Maybe I missed a subtle clue. Maybe I made a mistake that sent me down a wrong path for quite a while. I honestly don't recall. But the amount of effort it took me to determine the solution does not change the quality of the puzzle itself.

It didn't become an easy puzzle just because I found it easy to solve.

Similarly, there are a number of times where I managed to complete expert puzzles in times consistent with a medium or even an easy. Again, this does not change the fact that the puzzle was an expert level puzzle. It didn't become an easy puzzle just because I found it easy to solve.

Back to software

Looking at the variance in simple sudoku puzzles, I hope we can agree the same kind of variance is perfectly reasonable in software development. An estimate of 1 point indicates the team agrees this is a story of relatively low complexity and that it is similar in complexity to other stories that we previously agreed were also 1 point. An estimate of 1 point does not directly indicate that it will take a specific amount of time (or less). An estimate of 1 point does not necessarily indicate that it will be faster to complete than a 2 point or 3 point story. On average, a 1 point story will be completed in less time than a 2 or 3. On average.

A 3 point story doesn't become a 1 point story just because you completed it quickly.

There are times when a story changes. Say certain requirements are dropped or we discover that we'd already written some of the code months ago. I am sure there are other reasons. But just because a story took longer or shorter than the average time to complete similarly sized stories does not mean the story was improperly sized. A 3 point story doesn't become a 1 point story just because you completed it quickly.

It's All Relative

I recommend you use a reference story. Identify a story that the entire team can agree is 1 point. When you are estimating, keep that story in mind and attempt to estimate all others relative to it. Then, at the end of the estimating session, compare the stories to one another. Do the points still feel right? Compare the stories to random selections from prior iterations? Do the points still feel right? If not, make adjustments to your new estimates as necessary.