A product manager walks into your office and says, "We need a report that shows daily active users by region, broken down by feature usage, with trend lines for the past 90 days."

You nod. Sounds clear enough. You estimate it, add it to the backlog, and two weeks later you deliver exactly what was asked for.

The product manager looks at it, says "thanks," and then... nothing. It sits unused.

A month later, they're back asking for a different report with slightly different breakdowns.

What happened?

You built the thing. You didn’t solve the need. The request sounded like a problem, but it was actually a solution someone had already decided on.

The "I Need a Report" Problem

Here's the thing: rarely does anyone actually need a report. What they need is to make a decision, answer a question, or take action. A report is often one possible way to get there, but it's not the only way, and sometimes it's not even the best way.

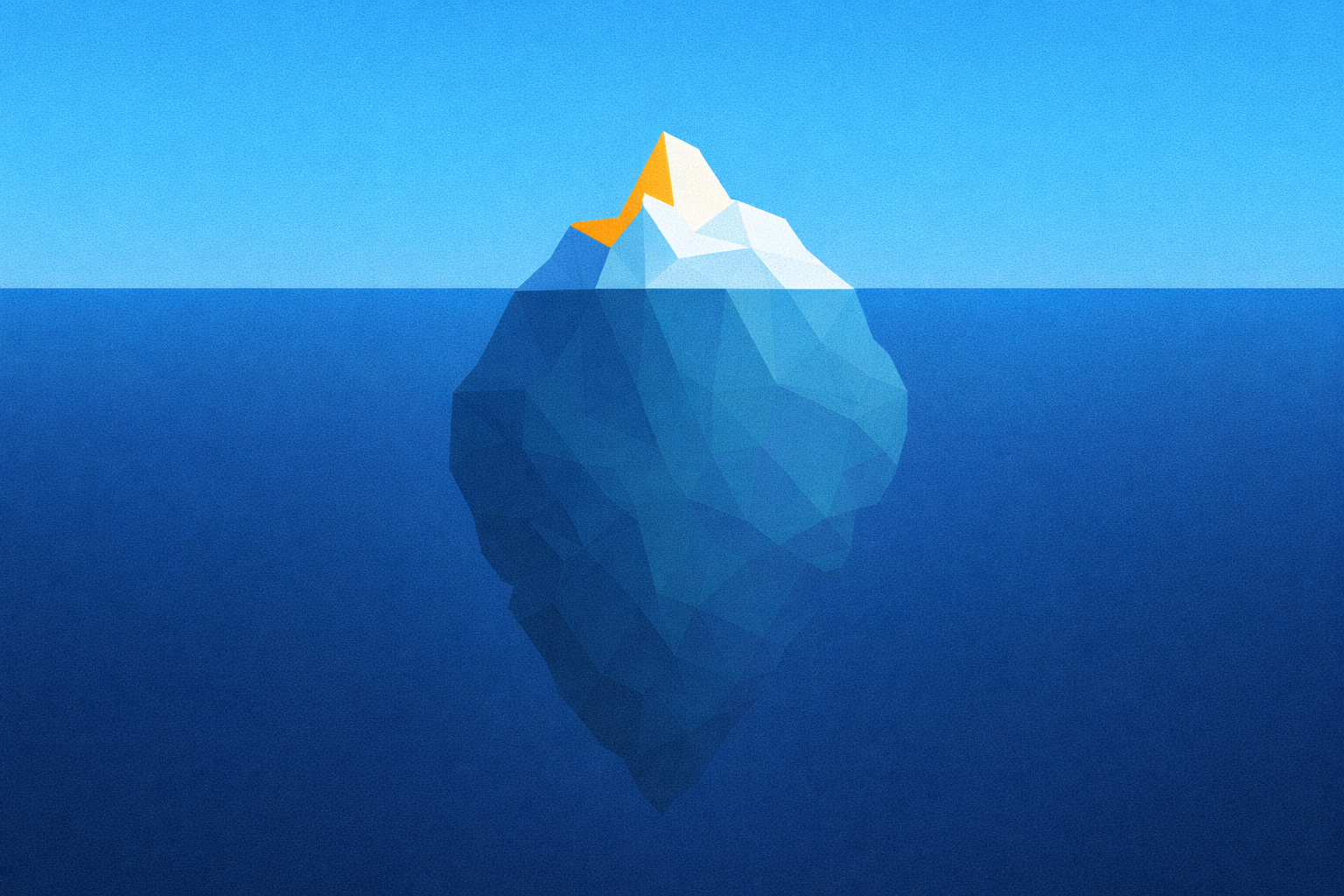

When someone says "I need a report," what they're really saying is "I have a problem I'm trying to solve, and I think a report will help." But they've already jumped to a solution without articulating the actual problem.

And when you build what they asked for without questioning it, you're building based on an assumption about what will help. You're one layer removed from the real problem.

This is why "knowing the problem you are solving" is the first behavior in the framework. You can't solve a problem effectively if you don't actually know what it is.

How Solutions Get Disguised

This pattern shows up everywhere:

"We need single sign-on." Maybe. Or maybe you need to reduce login friction for users who work across multiple tools.

"We need to expand into the European market." Could be. You need to grow revenue and there are multiple ways to do that.

"We need an API for our mobile app." Possibly. Or perhaps you need to give mobile users access to their data, and there are other ways to accomplish that.

People present solutions as problems because solutions feel concrete. They're easier to articulate. They feel like progress. And sometimes, especially when someone's been thinking about something for a while, they've convinced themselves the solution IS the problem.

But when you treat requests as requirements, you lose all the creativity and optionality that comes from understanding what you're actually trying to accomplish.

Peeling Back the Layers

So how do you get to the actual problem?

I usually start with: "What is the problem this is intended to solve?"

This question helps people step back from the solution they've fixated on and articulate what they're actually trying to accomplish.

"We need a daily active users report."

"What problem is this intended to solve?"

"I need to see if our recent feature releases are actually being used."

Now you're getting somewhere. The problem isn't "no report exists." The problem is "we don't know if people are using what we just built."

Another question I ask: "What would this enable you to do?"

This helps reveal the outcome they're after, not just the thing they think they need.

And when I want to understand impact: "What happens if you don't get this?"

This reveals how important the problem actually is and what the real consequences are.

"We need to expand into the European market."

"What happens if we don't?"

"Well, our growth has plateaued in North America, and investors are expecting revenue growth."

Different problem. It's not about Europe specifically. It's about demonstrating continued growth. Which opens up all sorts of other options.

Getting to Validation

Once you understand the actual problem, there are a few more questions worth asking:

"Once this is in place, what stories would you hear? What would the user say about this new feature?"

This helps people envision success in concrete terms. Not vague goals like "improved engagement," but actual things users would say or do.

"How could we objectively verify those stories?"

Can we measure it? Observe it? Confirm it actually happened?

"How could we know we accomplished it even without the user feedback?"

Sometimes there are leading indicators: things we can track before users ever say anything.

These questions connect directly to another behavior: validate before, during, and after. When you know the problem and you know how you'll verify success, you can iterate your way toward it. You can make smaller steps, check along the way, and adjust to new information instead of building the whole thing and hoping it works.

Worried it’ll sound like pushback? Frame it as risk reduction: ‘I want to make sure we solve the right problem the first time.’

A Real Example

I worked with a team that was asked to build a comprehensive dashboard for executives. The request was specific: real-time metrics on deployments, incidents, mean time to recovery, code quality scores, team velocity. The works.

This wasn't just a dashboard request. To make it happen, we'd need to roll out additional tooling across all teams, establish process standards for how metrics were collected and reported, and build the actual dashboard. This was a request for a major organizational change.

We asked: "What is the problem this is intended to solve?"

The answer: "I need to know which teams are struggling so I can offer support before things get worse."

That's a very different problem. The real problem wasn't "I don't have a dashboard." It was "I don't have early warning signals about team health."

Once we understood that, we had options. We could build the comprehensive dashboard and implement all the supporting infrastructure. Or we could set up lightweight check-ins. Or we could create a simple alert when certain thresholds were crossed. Or we could do regular team health assessments.

We asked: "Once this is in place, what stories would you hear?"

"I'd hear about a team that was struggling with deployment issues, and I'd be able to connect them with another team that solved something similar last quarter."

That helped us understand the real need: timely awareness and connection-making, not exhaustive metrics.

We ended up with something much simpler than the original request. A weekly summary email with a few key signals and a standing invitation for teams to request support. It took a fraction of the time to build, and it actually got used because it solved the real problem.

Why This Matters

When you confuse a feature request with a problem statement, a few things happen:

You deliver something that doesn't get used. Because it wasn't actually what was needed. It was just what someone thought was needed.

You miss better alternatives. Maybe there's an easier, faster, cheaper way to solve the actual problem. You'll never know if you don't understand what you're solving for.

You build the wrong thing with confidence. The clearer the "requirement," the more certain everyone feels. But false certainty is dangerous. You end up investing heavily in the wrong direction.

You disappoint people without understanding why. When you deliver exactly what was asked for and it still doesn't help, it's frustrating for everyone. The person who asked feels like you didn't understand them. You feel like you did everything right but somehow failed.

Making It a Habit

The good news: this doesn't require a massive process overhaul. It just requires a habit of asking questions before committing to work.

When someone brings you a request, especially one that sounds like a solution, pause and ask:

What is the problem this is intended to solve?

What would this enable you to do?

What happens if you don't get this?

Once this is in place, what stories would you hear?

How could we objectively verify those stories?

How will you know if it worked?

You're not interrogating them. You're trying to help. And most people, once they realize you're genuinely trying to understand, appreciate the questions.

Sometimes you'll discover the original request was exactly right. Great. Now you understand why, which makes everything easier.

But often, you'll discover there's a simpler path. Or a different problem entirely. Or that the problem isn't worth solving right now.

That's the value of knowing the problem you're solving. It gives you clarity. It opens up options. And it dramatically increases the odds that what you build actually matters.

Further Reading

Continuous Discovery Habits (Teresa Torres)

A comprehensive guide to ongoing product discovery practices, including techniques for uncovering real user problems and validating assumptions throughout the product lifecycle.

Explores the Jobs to Be Done framework for understanding what users are actually trying to accomplish, not just what features they request.

The Mom Test (Rob Fitzpatrick)

A practical guide to asking the right questions during customer conversations to uncover real problems instead of polite but useless feedback.

Opportunity Solution Trees (Product Talk)

Teresa Torres' framework for mapping problems, opportunities, and solutions to ensure you're solving the right problems.

How to Get to the Real Problem (Harvard Business Review)

Discusses techniques for problem diagnosis and avoiding the trap of jumping to solutions too quickly.